This is the wine that drew the world’s attention to the unclassified regions of Southern France and spawned a fantasy of winemaking as escapist lifestyle; the dream of a plot of land in the sun, blood sweat and wild nature bottled. In the 70s Aime Guibert and his wife abandoned Paris for the Languedoc buying a farmhouse with no intention of planting grapes on their land until a friend pointed out that its soil and microclimate were perfectly suited to vineyards.

This is the wine that drew the world’s attention to the unclassified regions of Southern France and spawned a fantasy of winemaking as escapist lifestyle; the dream of a plot of land in the sun, blood sweat and wild nature bottled. In the 70s Aime Guibert and his wife abandoned Paris for the Languedoc buying a farmhouse with no intention of planting grapes on their land until a friend pointed out that its soil and microclimate were perfectly suited to vineyards.

These days Mas de Daumas Gassac is frequently referred to as the ‘Lafite of the Languedoc’ and has established the region’s reputation for experimentation, modern winemaking and quality despite its lowly Vin de Pays status. Blended from predominantly Cabernet Sauvignon, with Merlot, Petit Verdot, Pinot Noir and Syrah all featuring in the 2007 assemblage (with other varietals brought in as Guibert sees fit year-to-year) the wine is unquestionably an iconoclast.

Tasting it for the first time, though, you don’t expect the predominance of Cabernet. Perhaps it’s because of the curve of the bottle but we’re pre-programmed to expect hearty, rustic Rhone blends from the bright hot lands of this part of France and yet this is all about the stately elegance of a Bordeaux pedigree. It has the inky violet hue and clear rim of young Claret with those familiar pencil lead and vegetal notes on the nose, only just permitting a suggestion of something of lesser breeding to follow through: leather and damp vegetation.

A little mean on the palate, the dark fruits and cassis are modestly enthusiastic, framed by cigar box sophistication but none of the underlying sweetness that characterises this style of Bordeaux. Unquestionably a little young yet, the finish strikes a slightly tart note of sour cherries.

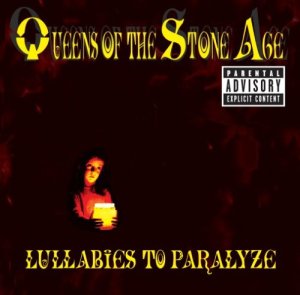

Perhaps it’s a wine too conscious of the styles it aspires to – a wine of the head and not enough of the heart. But everyone has a different opinion of where the head should give way to the heart. Admirers of Queens of the Stone Age, the Californian desert rock collective focussed around frontman Josh Homme – famed for their brand of robotic, heavy riffing and equally uncompromising approach to the off-duty pursuits expected of proper rock bands – ran up against the issue on the 2005 album, Lullabies to Paralyze. They’ve struggled to shake it ever since.

This was the first QOTSA record made following the ejection from the group of long-time bass player, occasional vocalist, songwriter and hell-raiser, Nick Oliveri. Immediately preceding it were two albums that are fairly unanimously considered amongst the best made in the genre in the last decade. Songs For The Deaf, on which they were joined by former Nirvana drummer and Foo Fighter Dave Grohl was certified gold in 2003. (Grohl isn’t the only superstar to have been attracted by Homme’s musical magnestism, more recently he formed Them Crooked Vultures, a project with Grohl and Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones.)

This was the first QOTSA record made following the ejection from the group of long-time bass player, occasional vocalist, songwriter and hell-raiser, Nick Oliveri. Immediately preceding it were two albums that are fairly unanimously considered amongst the best made in the genre in the last decade. Songs For The Deaf, on which they were joined by former Nirvana drummer and Foo Fighter Dave Grohl was certified gold in 2003. (Grohl isn’t the only superstar to have been attracted by Homme’s musical magnestism, more recently he formed Them Crooked Vultures, a project with Grohl and Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones.)

So, what happened between the magnificent Songs For The Deaf and the markedly less phenomenal Lullabies To Paralyze? Well, QOTSA lost Oliveri, its loose canon, it’s force of nature; a man prone to taking to the stage naked whose most undiluted contributions – songs like ‘Quick and to the Pointless’ – are the psychotic logical conclusion of The Stooges. There seems little question that his days were numbered and various rumours suggest that Homme (frequently portrayed as a control freak in the pursuit of this and other ruthless management strategies) was quite right to hand him his cards. Sadly though, with Oliveri went the band’s sense of wild, untamed force and where Homme’s rigorous, brutally clipped guitar playing and sense of structured restraint once gave the music an unbelievably taught forcefulness, without the suggestion of chaos it began to sound thin, dry and intellectual.

Homme is too great a talent to disappoint completely and Lullabies to Paralyze suffers most in relation to the magnificence of its predecessor. ‘Someone’s in the Wolf’, for example, is amongst his best, a spring-loaded dose of dread from somewhere deep in the forest of our fairy tale subconscious. But the album remains considered, subdued by structure and like the wine, too much of the head and not enough of the heart.